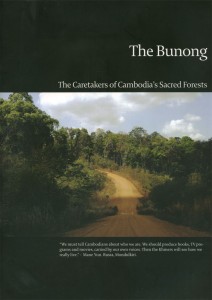

In 2006, I wrote a report for Fauna and Flora International (FFI) on the Bunong, one of Cambodia´s indigenous minorities. The Bunong live mostly in the north eastern province of Mondulkiri, an area of high barren plateaus, dense rainforests and virtually no roads, bordering on Vietnam.

Traditionally, the Bunong practice swidden agriculture and domesticate elephants. As there are hardly any elephants left in the wild in Cambodia, that tradition has already died. Today, their traditional farming lifestyle is also under threat – by missionaries, the loss of rain forest to mono-cultures and a huge influx of Khmer people into Mondulkiri Province.

The report was published in English and Khmer, primarily to create awareness within the Cambodian government and the business community for the plight of the indigenous people of northeastern Cambodia and for their ability to manage natural resources in a sustainable manner.

The fate of the remaining elephants in Mondulkiri is dependent on the continuing survival of the Bunong culture, which has since taken a serious beating from all the developments this report warns about.

The Bunong – Caretakers of Cambodia´s Sacred Forests was commissioned by FFI and co-financed by the EU, US AID, The NGO Forum on Cambodia, The Australian Government and the East West Management Institute.

This is Part 2. Read Part 1, Part 3 and Part 4 here.

All photographs by Aroon Thaewchatturat.

Part 2 – Cultural Diversity in Cambodia – The Bunong Contribution to the Kingdom of Cambodia

Religious Belief of the Bunong

South Asia is home to millions of so-called indigenous peoples. Nomadic or sedentary, most of these groups live in small self-governed village communities and practice subsistence farming.

Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, are all multi-ethnic societies with significant indigenous minorities. Speaking their own languages and following their own religious and cultural traditions, these groups have populated the remote mountainous wilderness areas of the region for millennia. Trade between indigenous peoples has always been a feature of life in South East Asia.

The majority of Cambodians are Khmer (about 90%). It is estimated that Cambodia’s indigenous people comprise about one percent of the country’s total population. Approximately 60% of people in Mondulkiri province belong to an indigenous group. Most of them are Bunong (54%), followed by Stieng (3%), Kreung (1%), Kraowl (1%) and Tampuan (1%). Ethnic Khmers make up 35%, Vietnamese 1% and Cham 3% of the population in Mondulkiri.

Most Bunong, like other hill tribe communities in the region, practice animism, the belief in natural spirits combined with ancestor worship. The older generation carries out more ceremonies, respects more taboos and knows more about the Bunong culture than younger Bunong.

As village elder Moe Chan recounts the Bunong’s Myth of Origin, the story of how the Bunong came into existence, to his family, his grandson Chok Marel is astounded – he’s hearing the story for the first time.

“Greengran lived below the earth. He gave a box of soil with seven worms and tree seeds to Jan, who created the world. Bong and Rong were brother and sister and Jan told them to get married. After much discussion, they agreed and amidst thunder and lightning, they were betrothed to one another. The couple made a sacrifice to calm the forces of nature and begat one child, which they also called Jan. The baby scattered the soil and the worms and seeds and mountains and sea and everything else on earth grew from this, except the really large trees. Finally, Jan took more seeds from Greenspan and created the really big trees. Then he proceeded to create animals, just two of each species. He gave the animals different voices, the most unique amongst them the elephant.

Finally Jan created another man called Prokong Tro Traluk, who sculpted a woman out of stone.”

Moe Chan laughs at his spellbound listeners, and continues with an expression of embarrassed amusement, “Prokong Tro Traluk laid the woman on the road. Another man, Ro-Un then rose from below the earth, lay down with the woman and all the Bunong, it is said, originate from this union.”

Grandson Chok Marel is determined to pass this tale on to his own grandchildren. Although aspects of this legend may appear outlandish and strange, the story shares many features with other myths of its kind, including stories from Vietnam, Thailand, Burma and Laos as well as stories from the Bible’s Old Testament. While the Bunong’s collective past is fractured by recent conflict and relocation, some animist beliefs and customs are upheld by almost every family and virtually every aspect of Bunong life is influenced by spiritual beliefs. What’s more, Buddhism in Cambodia has strong roots in animist traditions, and some Bunong, especially those married to Khmers, have started practicing Buddhism. In recent years, a small but growing number of Bunong have also converted to Christianity. One reason cited is poverty, as families don’t have the money or livestock to carry out the ceremonies prescribed by their old traditions. Also, a perception has been fostered that they will have better lives if they convert.

Adding to these existential woes, development agencies sponsored by Christian churches come to Mondulkiri’s indigenous peoples in ever larger numbers. Bunong who convert to Christianity abandon their belief in spirits, often cut down their Spirit Forest and consequently lose the conservation ethos at the heart of their culture.

Community life at the heart of Bunong culture

Just as important as respect for the spirits is village solidarity amongst the Bunong. Yat and Ngam, two village elders, are sitting on the veranda of Yat’s house in the village Putang, beneath a poster of King Sihanouk. Yat is tuning up his guong, a string instrument made from a hollowed-out gourd with a sturdy bamboo neck and half a dozen steel wires attached, unique to the Bunong.

Yat knows songs from all over the region.

“During the Pol Pot years, I was taken to a commune near the Lao border, where I learned to sing Mor Lam (Lao folk music style). I could not use the guong there. But nowadays I mostly sing Bunong and Khmer songs.”

As its dry season, some of Putang’s inhabitants are not working out in the fields and have gathered at Yat’s house. Women, children and a few elders sit in a tight circle, while Shamai, a 40 year old Bunong woman starts into song, accompanied by Yat on his guong. The songs of the Bunong celebrate self-reliance and virtue.

Robbery and laziness are mocked in song. Along the banister of Yat’s house, a row of wine jars stand lined up. A single long plastic straw is used to drink and true connoisseurs sip from several clay jars in a row.

As the sun sets over the village, other men and women break into song. Although most of the songs are about Bunong culture, some are topical and deal with historical issues, such as the Pol Pot years.

The event is very much a communal experience. While village elders Yat and Ngam clearly command respect, they are just part of the group.

But the strength of the community spirit is not just measured by good neighbourly relations. During the busiest times of the agricultural cycle when people have a lot of work like clearing old agricultural plots and planting or harvesting rice, villagers assist and help each other. In times of food shortage, villagers sometimes borrow rice or money from their relatives and go to the forest to search for resin, rattan, fruit, vegetables and, sometimes, to hunt. Solidarity runs deep in Bunong culture and crime is uncommon.

The Bunong and the Asian elephant

Central to Bunong culture is the elephant. Cambodia is one of the last countries in Southeast Asia that retains a sizeable population of wild and domestic elephants. The Bunong have always shared their lives with elephants, which are treated like humans. If an elephant gets sick or is injured, the Bunong will perform a ceremony and it is taboo to eat elephant meat. Prior to the Pol Pot years, almost every village had some elephants and the number of elephants owned by a family indicated their wealth and social status.

Moe Chan, the village elder from Pautrom, used to be an elephant catcher, “When I was young, we used to ride all the way to Vietnam to buy musical instruments. We used to catch a wild elephant with three or four domestic elephants. But the tradition died out a long time ago. The last elephant trainer who knew how to teach domestic elephants how to hunt and capture a wild elephant, died a long time ago. And I am one of the last catchers left.”

When the Khmer Rouge came to power and forced the Bunong to move to Koh Nhek District in the north of Mondulkiri, many elephants were killed by the communists, set free or sold by the Bunong. By the time the Bunong returned to their villages in the 1980s, the number of wild elephants had declined sharply. Furthermore, since conservation efforts were introduced in the mid-1990s, it’s forbidden to capture them.

Today, it is thought that the Bunong own no more than 100 domestic elephants. Some Bunong believe that having a baby elephant makes the spirits angry, others perceive a baby elephant as good luck and a marriage ceremony for the elephants is arranged. Nevertheless, elephants rarely get opportunity to breed and are likely to disappear from the villages of Mondulkiri in the next twenty years.

Moe Chan is realistic, “The Bunong have always used elephants for transport of forest product, rice or to visit relatives and I guess the motorbike will do that in the future.”

He smiles sadly, “But of course the motorbike cannot go everywhere in the forest.”

The remaining pachyderms owned by the Bunong are most likely to find employment in Mondulkiri’s burgeoning tourist industry.

The Bunong Healers – champions of traditional medicine

Cultural diversity is no more obvious than when looking at a community’s medical practioners. While Cambodia is slowly rebuilding a basic infrastructure of health posts and hospitals, many Cambodians continue to rely on medicinal plants and traditional remedies, some effective, others less so.

The only plants for medical treatment which are known by the majority of Bunong today are used in cases of diarrhea or lack of energy. However, the village shaman’s (traditional medical practioner) knowledge is much broader, as he/she collects many different plants to cure people.

If the connection between the Bunong and the forests of Mondulkiri is lost, this valuable and unique medicinal heritage will be lost to Cambodia. Respect for the spirits, village solidarity and ancient knowledge all contribute to the cohesion of the Bunong community as well as to Cambodia’s wealth of cultural knowledge.

This is Part 2 of The Bunong – Caretakers of Cambodia´s Sacred Forests. Read Part 1, Part 3 and Part 4 here.

1 thought on “From the Archives: The Bunong – The Caretakers of Cambodia´s Sacred Forests – Part 2”