The Andhra fishermen of Puri on India’s east coast are fighting for cultural, financial and spiritual survival.

First light on Puri Beach. Pentacotta fishing village, which grows like a misshapen appendix from the resort’s northern beach front, is coming to life. More than 10.000 people from Andhra Pradesh live in small one-storey stone and mud houses with thatched roofs, little electricity and no sanitation.

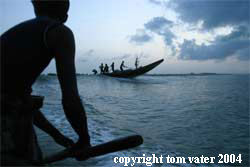

The beach is lined with hundreds of boats ready to brace the uncertain pre-monsoon weather. Thick clouds are rolling out of a gray dawn and the breakers crashing into the shore are foaming. In another couple of weeks, the rains will make trips into the Bay of Bengal near impossible.

Tata Babu is just 23 years old and commandeers one of the boats.

“Namaskar, good morning, we are getting ready to leave, to make an early morning catch.”

The young man is excited, “We have a new engine, first time today.”

Babu gathers his crew of six. The men, dressed in torn shirts and lungis carry nothing but their lunch in metal pots. Other crews assemble around their vessels. It takes more than twenty men to carry the heavy boats down to the water’s edge.

“There are twelve people in my crew. But usually only five or six of us go out. At the end of the day, we share the catch amongst the whole group.”

Babu shouts for his men, they are ready to go. The crew, up to their waists in the breakers that role in from the Indian Ocean, are pushing the boat into the surf.

One by one they jump on board. The driver, Dos, lowers the screw into the shallow water and cranks up the new engine. The boat jerks forward, the next outsurge carries us into open water.

A second boat stays close by. Babu waves and shouts across. “One net for two boats, we drop the net and then pull it in from two sides.”

A mile off the Indian coast, the two boats separate. The net, almost a kilometer long, drops into the dark water between them. The boat falls silent. Sette, a wild looking thirty-something with curly hair and a shirt that reads ‘GAP’, has a plastic bag wrapped in his shirt, containing matches, bidis and chewing tobacco. The men light up and watch the sun rise.

Orissa, one of India’s poorest states, has a population of over 35 million. Agriculture is the staple income and Oryans have never taken to the sea, despite a seven hundred-kilometre coastline rich in fish stocks. The British first introduced fishing in Orissa by encouraging fishermen from Andhra Pradesh to migrate to Puri in 1866. In 1956 another wave of Andhra people followed. Many of the inhabitants of Pentacotta village still have contacts to their home state and Babu makes several trips a year to se friends and relatives. As the fishermen from Andhra only marry within their own community, men regularly visit their southern communities to look for suitable wives.

The Andhra fishing communities are Hindu but their prayers are unique. Gods of the sea are offered sacrifices in the shadow of long bamboo poles, lined up in untidy bundles along the shoreline in front of the huts. Old inhabitants of the community, both men and women, are often sought after as mediums to communicate with spirits or deceased family members.

Babu arrived in Puri when he was six years old. “My uncle moved here with me and when I was thirteen, I went to sea.”

He remembers the first trip, “I was sick as a dog. But I got used to it quickly.”

There is little other work in the area. The men become fishermen and the women transport the daily catch from the beach to the factory or waiting trucks headed for the fish markets in Calcutta and Mumbai.

As the sun rises in milky clouds above the coastline, the crew signals to the second boat and starts hawling in the net. Dos, wrapped in a plastic sheet, pulls in the line with the markers.

“There are many jellyfish in the water.” The forty year old shows me his arms, covered in small pimples, caused by the stinging tentacles of the large brown invertebrates. Babu adds that some men have been killed by particularly vicious species.

The net is slowly pulled in and the six men take turns to free the meager catch from the line. Mackerel, small catfish, young sharks, hammerheads and reef sharks, and the odd puffer fish flop across the deck, but thirty minutes later, as the boats reconnect, barely ten kilos lie on Babu’s deck.

The sun is up; the now placid water reflects heat already. The two crews tie their boats together and head further out to sea. The Jagannath temple, Puri’s highest building slowly disappears in the distance.

Babu shouts, “Enough.” and the boats separate. Every move by every man on board is professional, well coordinated and never wasted. Pulling in the nets is extremely hard work and working days are up to 16 hours long. The crew, all good friends who help each other wherever they can, have little to say as the air around them heats up.

It’s never enough. The fish from Pentacotta village are in such high demand that the buyers are always waiting on the shore. Yet, the fishermen, who sell by the boatload, rather than by weight, barely get by. Impromptu auctions spring up on the beach whenever a ship comes in. Prices are negotiated between several buyers and the crew.

“I earn 200 Rupees (5$) on a really good day. A good catch is 10.000 Rupees (250$). Fuel and food cost us 2000 Rupees. The remaining 8000 Rupees are split between the boat owner and the crew – that means 4000 Rupees amongst ten or twelve people, on a good day. After I get my wages I have to pay debts.”

The boat owners are fishermen themselves and there are few in the village that own more than one vessel. The boats, around ten meters long and four meters wide, are built by Oryans, at 40.000 Rupees (1000$) a piece, the diesel engine another 20.000. If weather or time allow, a sail is hoisted and the precious fuel is saved.

Like many men, Babu dreams of owning his own boat one day, sitting back and running a crew.

“I owe the boat owner 8000 Rupees because I married the girl I loved. She brought no dowry into the family and I had to borrow the money for the wedding. It will take me years till I have paid my debts and am free.”

Sette and Dos laugh from the stern, “Maybe his entire life. Babu does things his way. That’s why we like him.”

Arranged marriage is the norm amongst the Andhra community. Babu has been desperately looking for alternative income opportunities. “To pay off my debt, I went to Calcutta and worked in a factory processing prawns. It was hell. I earned 2000 Rupees (50$) a month, but the shifts were too long, sometimes 20 hours.”

It’s hard to imagine a job that would be too hard for this fisherman.

”I came back to Puri after one month and started fishing again.”

Babu and his men are perfectly at home onboard their boat. As the sun beats down with unforgiving force and the net is waiting for its prey, Dos and Sette fasten a piece of black tarpaulin to a couple of rudders to make a sunshade. There’s only enough room for three men under the awning. The rest linger in the sun, keeping their heads down as best as they can.

By midday, Babu is ready to throw in the towel, “We are not doing too well today. It’s hot and the net comes in almost empty. Maybe we should head back to the village.”

The men are distraught. Most of them have to feed large families. The fishermen go out every day, weather permitting. Even so, it’s a struggle. Sette and Jagdes separate the catch into meager piles – eight small sharks, a dozen mackerel and an array of smaller fish is all they have to show for their efforts. They have been out for almost eight hours. The second boat has also had enough, but Babu decides to give it one more shot and the other men give in. The net is rolled overboard once more. The waiting game in the blazing sun zaps the last of the crew’s energy. Half an hour later, the men pull in the net. It comes up mostly empty.

Suddenly Babu shouts, “Dos, start the engine, let’s go Let’s go.”

The crew springs into action. Sette and Jagdes dump the retrieved net overboard and the boat lurches further out to sea. In the distance, no more than a mile east, two other boats are bobbing in the waves, closing in on each other, separating yet again, moving swiftly across the water. Babu, one of the paddles held high above his head to catch the attention of other boats in the area, stands in the bow, surveying the sea ahead. As we catch up with the other boats, the color of the Indian Ocean suddenly changes from dark blue to brown. The surface is churning. The noise of boat engines, acrid diesel smoke and the cries of the fishermen fill the air. Babu signals frantically for more support. His boat has started quickly circumnavigating the two other boats. We are closing in. There are so many fish in the water around us that it almost looks feasible to walk across their backs to the nearest vessel. The two early arrivals have dropped a small strong net between them and are scooping up the shoal of catfish that is frantically trying to escape, darting this way and that, panicked by the engine noises and the men’s shouts. More boats arrive, all circling the first two vessels. Dos and Sette jump ship – it takes all the power these men can muster to hang on to the net churning with desperate energy. The catfish, plump and half a meter long, must weigh ten kilos each. And there are thousands.

A few minutes later I am alone onboard with Jagdes. The others have all jumped ship. Not happy with just one haul, the hunt is on for the entire shoal. Eight or so boats have now converged on the spot of churning ocean. The vessels move in ever tightening circles while more nets are prepared. The men wear grim expressions, focused on the hunt, their rare chance to come home with a full load. A pitched battle off the coast of Puri is in full progress – unforgiving, it’s a battle for survival, both for the fish and their hunters.

The first boats have pulled the net so tight, there are barely two meters between them. The net is bulging, spilling over. The men onboard begin to shovel the catfish on deck with their paddles. But there are too many fish and their spiny dorsal fins are dangerous. There is barely any room on deck, flooded with writhing fish. Dos and Babu are beating down on the catfish before kicking them down into the hold, which is overflowing within minutes. The deck is awash with blood. Some fish manage to slide back into the water, but the youngest boys jump in after them and catch the stunned fish with their hands, dragging them back to the boat. Many fishermen have lost limbs like this – sharks are never far off with so much blood in the water.

The next couple of boats are lined up and more are cruising in circles. The shoal is still gigantic. Babu jumps back on board. He is beaming, “The first eight boats own this shoal. I think we will manage to catch all of them.”

He cranks up the engine and we chase across the water, boiling with life.

The battle rages on for several hours. In the afternoon, as the shadows get longer and the men get tired, Babu remembers the net his crew dumped in open water hours ago.

He signals another boat to take over and we head back towards the mainland. He’s done his share. The crew’s sense of direction is perfect and a few minutes later, accounting for current and time, the net is spotted and pulled in. No one is bothered now that it’s coming back matted with jellyfish. It’s been a good day for Tata Babu and his men.

Tired, the boat limps back towards Pentacotta village in the late afternoon. Twelve hours in the Bay of Bengal and the men look weary.

“Tonight we will have a drink. And tomorrow we will make a sacrifice to the gods of the sea. It’s been months since we had a catch like this.”

By the time we race through the breakers to shore, the catfish have been sold and hauled off to the factory. The boat is pulled in, the net is cleared off the deck and the meager morning’s catch is dumped on the beach.

On the beach, the men quickly prepare a sacrifice for the gods.

“We pray for Ganga, our sea god, to give us a catch like this again tomorrow.”

Several coconuts are opened, the milk spilt into the sand. A chicken is waved towards the foaming surf and quickly decapitated. Blood mixes with the coconut juice. The crew is ready for the next day.

”I need catches like this every day if I am ever to pay off my debt,” Babu muses. “Tomorrow at 5am, we’ll be out there, hoping, watching the ocean, praying for another miracle.”

Babu looks worried, “Ten years ago, there were a lot more fish and we did not have to go so far out. These days, it’s much harder. Sometimes we catch nothing at all.”

Published in Untamed Travel and Traversing the Orient Magazine