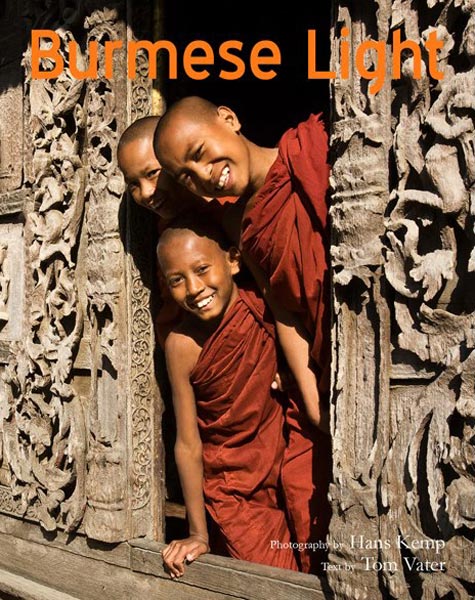

My account on how I wrote Burmese Light, the illustrated book by photographer Hans Kemp in InDepth Magazine.

Read the story on pages 20-23. Or read it right here…

It really hit me while I was walking amongst the giant stone ruins of the former kingdom in Mrauk-U, which ruled much of Burma from the 15th to the 18th century, accompanied by a seriously eccentric Burmese who called himself Radioman, aman who had gained enough notoriety in this remote cultural gem to make the pages of Lonely Planet.

The temple ruins, stupas and palaces of Mrauk-U are nestled amongst rolling green hills and rice paddy, dripping with moisture, populated by giant yellow locusts. The local town sits amongst the ruins like a recent arrival, slowly spreading itself over another culture long gone.

Welcome to Arakhan, nowadays Rakhine State, a place that has seen relatively few foreign visitors in the past half century. Here, travelers could be forgiven to have hopes of discovering last frontiers and places so remote they have not made the pages of Wikipedia yet.

At the end of a long day’s walk, Radioman handed me a letter which contained a long wish list of books and magazines I was to send him. He had hand-written not one but two copies of the letter, which was a couple of pages long, despite my assurances that I would not be able to send books to Mrauk-U. That didn’t seem to bother him. The otherworldliness of his home town had consumed him. I was also utterly consumed and touched by the color and pace of Mrauk-U.

Rudyard Kipling famously wrote: “This is Burma and it will be quite unlike any land you know about.” Looking over the chedi spires of the barely remembered kingdom, blackened by age, I quite agreed.

But amongst those same moss covered chedis, another side of Burma lurked in the brush. Everywhere I went, I encountered heavily armed military, ostensibly protecting the local Buddhist population from an imminent Muslim attack, I was told over and over again. The only Muslims I encountered were frightened traders in the market in Sittwe, the state capital. The Rohingya fisherman who used to deliver their catch to the docks there had disappeared in the wake of a vicious pogrom.

I had set off for Burma in August 2012. My assignment: to write the text for Burmese Light, the illustrated book project by Dutch photographer Hans Kemp published by Visionary World in Hong Kong. I decided to write the bulk of the text as a first person narrative, following in the footsteps of other literary travelers – most notably Rudyard Kipling and George Orwell – whose quotes provided the introductions to the book’s main chapters.

Following my trip to Mrauk-U, I returned to Yangon and explored its architecture, bookshops and restaurants. Expectedly it rained much of the time and the old British buildings which loomed into a gun metal sky, were covered in the same mold as the ones a little to the east in Kolkata. But Yangon was no crowded urban hell.

Rather, the former capital was a pot holed city waiting to be fixed, dotted with magnificent colonial edifices and pagodas and countless tea houses, rather quaint and quiet. There were no motorbikes and few cars on the streets. Malls and international banks had yet to make a concerted appearance. No doubt some of the old architecture would soon make way for chrome and glass palaces, but back then the former capital exuded dilapidated charm. The past, both colonial and post independence remained visible everywhere even as the future was moving in.

Up-country I traveled around Inle Lake and explored its shore-side dawn markets and Shan shrines. I visited former capitals around Mandalay, explored the city’s fascinating jade market, and rode an old river ferry down the Irrawaddy to the magnificent ruins of Bagan.

Burma is a predominantly Buddhist nation, but as elsewhere in Southeast Asia, older beliefs have been absorbed into the dominant faith. The pre-Buddhist Nats, 37 spirits of the elements and nature, are revered and celebrated in most of the country but nowhere more so than around Mandalay. In summer, several festivals honoring the Nats take place.

I made my way to the Taungbyone Nat Festival an hour north of the city. As in Mrauk-U, I had the feeling of reaching a kind of frontier, though this one was less of a geographical dimension, rather one of the mind. Hundreds of spirit mediums set up shop in pavilions around the festival site where they fell into exuberant trances to the sounds of super-sonic acoustic orchestras and the chanting of both male and female singers. Most of the spirit mediums were transvestites or transsexuals and many of the male devotees were gay. A kaleidoscopic world crammed with beatific moments emerged during three days of dances and marathon fortune telling sessions. The absence of any concessions to foreign visitors reminded me once again of Kipling’s quote…”quite unlike any land you know about.”

Fast forward to November 2015.

The country has gone to the polls, the military junta has been trounced in national elections and a new chapter has begun for the country, one a little more complicated than the ambiguous limbo Burma enjoyed between 2011 and today.

The economy is booming but the flood of smart phones and cars in ramshackle Yangon represent the ominous arrival of globalization in all its beautiful terror. Mrauk-U has temporarily sunk back into obscurity in the wake of rising nationalism in Rakhine.

But not all is lost.

For the first time in a half century, ordinary Burmese have an opportunity to participate in the destiny of their country. Infrastructure development, lasting peace in the border areas, and reconciliation between faiths should be top priorities. The country has reached another crucial junction in its turbulent journey. Hopefully, it will travel towards the very special light it is blessed with.

Burmese Light indeed.

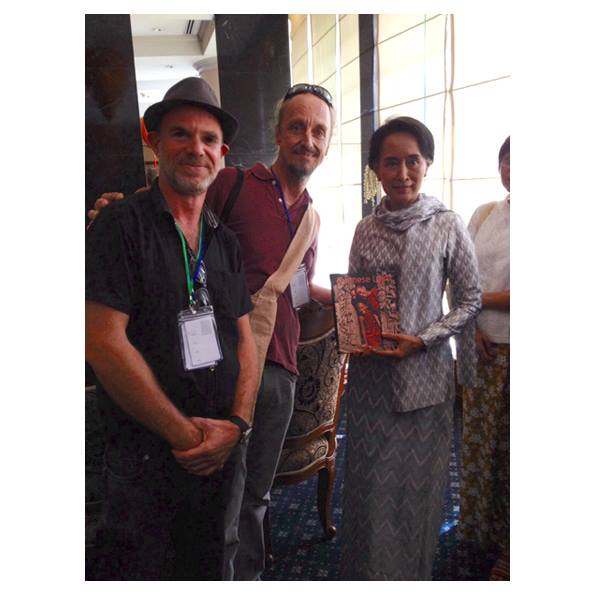

Hans Kemp and I present Aung San Suu Kyi with a copy of Burmese Light at the Mandalay Literary Festival in 2014.